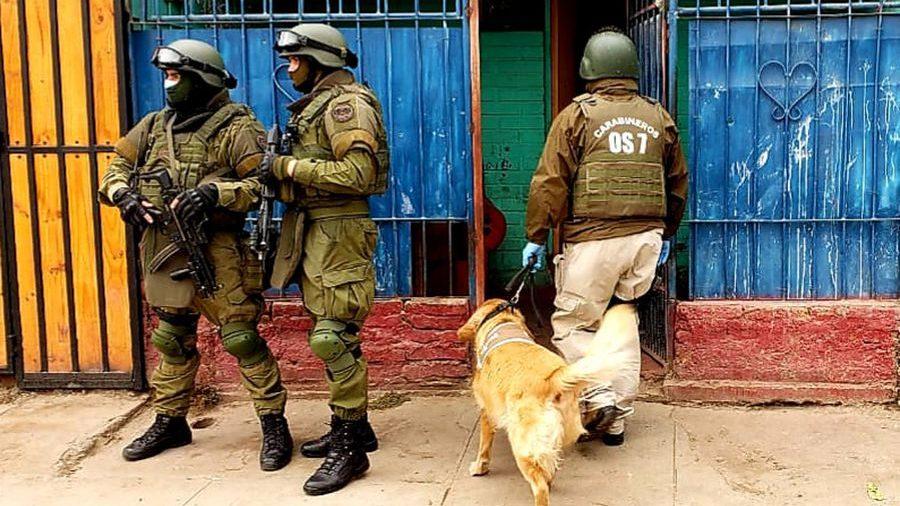

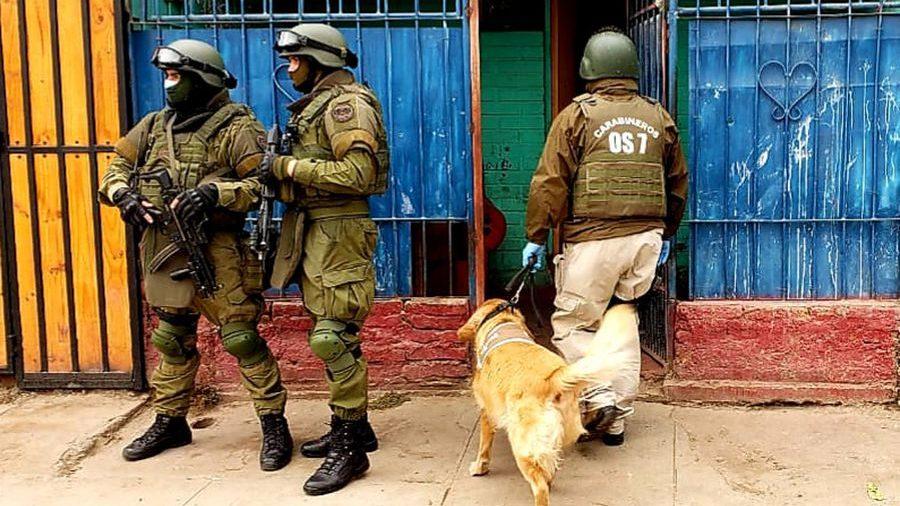

El autor argumenta que dividir el mundo entre buenos y malos no ayuda a entender el problema del narcotráfico ni a reducir su violencia. Usando literatura reciente muestra cómo el crimen organizado y la legalidad (policías, jueces, políticos y todo lo que en esta guerra se entiende como el bando “bueno”) se articulan en una “zona gris”. Esa articulación es mucho más extensa y frecuente de lo que creemos. Dicho en breve, más recursos para policías pueden fortalecer a un crimen organizado que se ha especializado en infiltrarlas ¿Entonces qué hacemos? La columna invita a mirar el problema con más argumentos y menos prejuicios.

These days the problem of "narco" emerged again on the news and political agenda.The greatest social visibility of the narco also gave a new boost to bills for the fight against organized crime.Comparative experience about the situation of organized crime in Latin America calls into question a series of assumptions that underlie our diagnosis of Chilean problems and public policy proposals in debate.In this note I identify three problematic assumptions about the nature of the phenomenon.In an upcoming note, I will raise objections to some public policy proposals that are raised as "silver bullets" to solve the problem that Chile has today.In both, I discuss the assumptions underlying the debate based on comparative experience.

Assumption 1: clear demarcation between institutionality and organized crime.

A classic work on the process of formation and consolidation of the State "Yankee" persuasively argues that the US was born as "a country of smugglers" (Peter Andreas 2013). According to Andreas, smuggling played an essential role in the American independence process. On the other hand, after its independence the smuggling state began to chase smuggling. Its clerous customs political allowed to finance the treasury and consolidate state construction. In analytical terms, what Andreas allows us to understand is that the relationship between state actors (institutionality) and "illegal" activities is strongly contingent (it changes through time and space). And this relationship also pivotes in political decisions regarding what is considered legal or illegal. In other words, states explicitly define what is legal and what it is not; thus constituting illegal legal markets and markets, as well as instituting incentives for actors that seek to undertake both types of market. The manido case of the prohibition in the US and its consequences constitutes a classic case.

Why is it important to understand the strongly political nature of the constitution of illegal markets?Because our natural tropism questions to think of a clear distinction (and separation) between good and bad;among those who are with legality and those who violate it.And because it also returns responsibility to the field of good: politics.This does not mean that the solution to the problem is not merely political, nor to maintain that there are no other causes that operate in favor of the expansion of illegality.However, politics is central.

If Andreas allows us to problematize the clear demarcation between the legal and the illegal based on the political origins of both sands, the dim demarcation between them, it also manifests itself in the street;through the uneven validity of the rule of law in specific territories and areas (activities).

Analyzing the constitution of “clandestine orders” around the operation of the auto parts (stolen) markets and the informal market of the salty in Buenos Aires, Matías Dewey (2015) clearly illustrates the selectivity with which state agents apply the law.Police and justice agents, according to Dewey's analysis, contingently negotiate with political and criminal actors to whom the law is applied, and who is not.These negotiations generate "released zones" and "protected areas", which can be reconfigured based on new negotiations and an alteration of the foundations of a protection pact.(See Matías Dewey in Ciper).

Police “boxes”, whose coffers grow with the bribes that lubricate these pacts, not just enrich the police.They also finance political campaigns or disrupt them, creating security crisis in districts whose leaders are resist to agree.And in turn, the "boxes" sometimes end up financing basic supplies for the operation of the police stations, such as the ink with which complaints are printed on theft of cars with which the victims go to insurance companies.Dewey's evidence also suggests that insurers agree to installments for vehicle theft, associated with the release or protection of zones, in order to limit their liability within reasonable profitability margins.

Dewey's work suggests that the validity of the rule of law in a given territory or market depends strongly on the negotiation between actors that we presume as "legal" (police, judges, politicians, insurers, clothing brands whose property rights are violated bycounterfeiters, etc.) and “illegal” actors (cars thieves, reshiers of spare parts, counterfeiters, owners of factories that work based on the exploitation of child or migrant labor, etc.).

A more recent work, published by Javier Auyero and Katherine Sobering (2019) proposes the concept of "state ambiguity" to account for this same type of configuration.Analyzing transcripts of judicial records, the authors illustrate the strong penetration of the organization of organized crime in the police and politics.The infiltration capacity of the police, through the payment of tenths, is associated, for example, to advantages for one or another band.In a classic mechanism, the infiltrators "deliver operations", so that when police or judicial procedures are planned, they end up failing.

In another usual mechanism, the bands that achieve greater infiltration, use the police and justice in their favor, to advise blows to rival gangs and consolidate territories or markets.According to a recent work by Guillermo Trejo and Sandra Law (2020), that same mechanism would explain the security crisis in contemporary Mexico.

In the same vein, proposing to assign more resources to the "good" to combat "bad" seems a logical solution from an analytical perspective that conceives organized crime in black and white.The problem is that organized crime and legality are articulated in a "gray zone" (Auyero 2007).From that perspective, inject resources (such as weapons, budget, or even new legislation that increases the power to negotiate actors who participate in the gray zone) can end up throwing benzine into the fire.The characteristics of that gray area, and the actors and institutions that constitute it vary between countries, territories, and temporary periods.But the existence of the gray zone is consubstantial to any reality in which organized crime is consolidated.

Thinking about a clear demarcation between legal and illegal is reassuring.To maintain that there are "released zones" in which the State does not enter, it means denying the political and institutional reasons that are consubstantial to such liberation and its persistence.In the areas released, the State and its agents are present, but apply the law selectively and contingently, according to gray zone agreements. In the released areas, state actors are many times less legitimate than criminal actors, but that illegitimacydoes not derive from his absence;but of a gray and ambiguous presence.Even assuming that today non-state actors have been consolidated with territorial control, it is necessary to understand that in inter-temporal terms, the "released zones" are the product of previous political decisions that set said territorial control.

Assumption 2: The narco is the main problem and is in the populations.

A second relevant assumption is that the fundamental problem is the narco, and in particular, microtrafficking.This assumption is consistent with what we know regarding the profit margins generated by the drug business, as well as with the expansion of the market that it today has in the world and in Chile.In addition, the expansion of the phenomenon in territorial terms, as well as the increasingly frequent presence of violent irruptions, have given greater visibility at the social level.However, conceiving and defining the problem in this way limits our ability to understand and dimension it.

On the one hand, the narco is not only or mainly micro-trafficking.The narco involves at least four different activities, chained by multiple logistics links in which different types of actors operate: production, macro-trafficking (international shipments and wholesale), micro-transfrafic, and money laundering.If we think that the narco is micro-trafficking and that occurs mainly in populations, we are stopping understanding again.Even if we are only interested in micro-trafficking, the focus on populations would leave the mechanisms by which the drug is distributed in the consumer market where greater profitability is generated: the Alto neighborhood.How Marcelo Bergman (2019) points out by verifying that at the level of Latin America the narco expands with the formal economy and economic growth of the last and a half decade: "More silver, more crime (organized)."

In other words, a focus exclusively on micro-trafficking in populations leaves large players in the narco market out of the scene, who benefit from higher income is through the control of routes and deposits for the macro-trafficking or the profits left by washing (another activity, by definition, of gray zone). Production, an activity for which Chile would not have natural conditions and whose income has traditionally been low, has also changed radically in recent years with the progress of synthetic drugs and with the proliferation of “kitchens” of coca and synthetic in urban areas in urban areas . In some countries, such as Bolivia and Argentina, that change in business logistics is not only reflected in the growing arrival of chemicals used in the different manufacturing process (which incorporates as potential participants of the business to laboratories, pharmaceuticals and legal companies that They operate with these chemicals), but also in patterns of hydrocarbons consumption, electricity, and white line goods such as microwave and washing machine (all used in kitchens to stretch cocaine or create synthetic products).

On the other hand, the main problem is not the narco, nor the drug, but the articulation of organized crime. Once organized crime actors are constituted and gain power (and eventually, social legitimacy) the business can be anyone. In Colombia, in a context scheduled for a high international demand and the concentration of government repressive effort in the eradication of coca, organized crime actors began to expand and technify illegal gold mining; Achieving for a period, greater profits than with the export of cocaine. In Peru, mining and illegal logging also generated ample space for the consolidation of powerful organizations. Also in Peru, in urban areas, the economic boom resulted in the massive expansion of construction. And there came organizations that began to derive substantive profits through extortion to construction companies. When the State began to control this market, the same organization resulted to other businesses such as extortion to schools, generating a mechanism for obtaining scarce quotas in private schools. In Paraguay and Uruguay, the same bands that smuggled cigarettes, whiskey and consumer goods, and that controlled "the gray zone", began to invest in drug shipments. In Mexico, several of the large posters have diversified today in the control of the avocado, lemon market, and the theft and sale of gasoline.

Extortion and security tax, as well as the micro-credit to small merchants constitutes, historically, one of the main businesses of organized crime.So is the management of the illegal game (are the slots that we see today in every business and chopped neighborhood?) And the allocation of informal positions in fairs and markets.Property take and occupation (land and houses), as well as the hired, traffic of people and protected species (one of the most lucrative businesses currently) also constitute activities associated with organized crime.All these activities have their articulation in gray zone spaces, although they are only tangentially linked to narco and micro-transfrafic.

The possibilities of diversification are multiple and change constantly.In some cases, as in the modality of "drugs by drugs" on the border with Bolivia, two illegal markets are integrated (that of the theft and smuggling of cars to Bolivia and that of the entry of cocaine from Bolivia by the dry border).In other cases, integration occurs between an illegal and a legal activity.As an example, think about the growing confiscation of drug shipments from Peru in covers and vessels formally dedicated to fishing.

The integration of legal and illegal businesses is inherent in the washing activity.And there is also a horizontal and vertical diversification of business possibilities.The pressure on money laundering encouraged the sophistication of washing mechanics.Those who today wash assets by buying real estate or cash vehicles are mere fans.Investment in formal commercial premises (think of a sushi, a botillery, or a neighborhood mini market) is a step forward in sophistication.The same applies to the washing associated with markets whose prices or transactions are difficult to establish and monitor (how exactly is the pass of a soccer player worth? How much does a neighborhood religious entity collect for “tithes”?).However, the more settled and powerful the organized crime becomes, the more its sophistication and integration progress with the formal economy.

In sum, reduce the challenge of organized crime to the narco, and specifically to the narco-mood in the populations is equivalent to not wanting to understand the problem in its real dimension and in its implications.Violence in populations is real and affects the lives of millions of compatriots who must survive in the gray area.But to think that organized crime is just that, it also implies criminalizing and responsible for the weakest link of the chain for a much more complex problem.Our prisons (and growingly, our cemeteries) are already full of those who are part of that last link.A very significant proportion of those who are deprived of drug trafficking in Chile are poor women.However, the business remains prosperous.

Assumption 3: Organized crime generates violence.

We usually associate organized crime, or narco, with violence.The issue emerges on the public agenda only when openly violent facts reach the information pattern.However, organized crime lives on order and stability.Both guarantee the business, without attracting attention.Colombia has consolidated itself, in recent years, as one of the main drug exporters in the world.However, we have not heard of a new Pablo Escobar, or a new Cali cartel.The so -called Narcos 3.0, Piola pass.And they have achieved a level of sophistication in their financial logistics and intelligence that has eventually made them undetectable.

Condestine orders are in this sense mechanisms that reduce violence (through corruption and negotiation of protection pacts).They work and consolidate because once a criminal organization with some territorial control is established, they allow to balance their interests with those of the State agents and the political authorities.Of course, in normative terms, clandestine orders are execrable.They also generate structural violence and derive in the inefficient functioning of the economy and institutionality.But they reduce the violence and social visibility of the activity.And besides, they are very profitable.

In a text that maps the origin and evolution of the narco in Mexico, Ioan Grillo (2012) also presents evidence on this point. The narco in Sinaloa began operating towards the end of the 19th century, when Chinese immigrants, working on the construction of the railroad in the area, imported the poppy. From Sinaloa, at the beginning of the 20th century, the New York and San Francisco Opium Markets were already supplied. The history continues with the illegalization of opium in the US first, and with the expansion in Mexico of marijuana plantations, during the second half of the 20th century. Mexican opium and marijuana continued to supply the now illegal American market without major problems. During the Nixon government, for example, USA for the first time implemented the crop fumigation policy in Mexico (the same policy that would apply, much later, in Colombia). The gringos did not calculate that the same government that had agreed to implement fumigation, had also implemented mechanisms by which it was feasible to transform herbicide into fertilizer.

Why do we only hear about the Mexican narco in the last fifteen years? During the 20th century, the PRI's power structure regulated efficiently, in terms of violence control, organized crime activity. He did, of course, with high levels of corruption. The PRI out of power broke the pre -existing protection pacts that regulated the market. Together with the extension of the business and its margins (which derives, in turn, from the closing of the Caribbean route where the Colombian drug arrived in the US in the 80s, and of the consequent increasing centrality of Mexico and Mexican organizations in The new routes), the fall of the Mexican clandestine order resulted in a spiral of violence between bands that began to fragment and compete for the market. Soon, open violence is not consubstantial to narco or organized crime. The spirals of violence indicate, in reality, the presence of relevant disruptions of the clandestine orders that supported the criminal activity.

In a recent text, based on empirical evidence on the cases of Colombia and Mexico, Angélica Durán-Martínez (2018) argues that the visibility of violence does not depend in the first instance on the actions of the bands, but on the cohesion of the apparatusState security.According to Durán-Martínez, a cohesive security apparatus becomes more reliable and stable two little violent balances.On the one hand, a cohesive security apparatus can guarantee the rule of law and state coercion, reducing the incentives of organized crime to operate violently and constraint its expansion.On the other hand, a cohesive security device can also establish a stable clandestine order and therefore corrupt, but not very violent.

Thus, according to this analysis, violence is more associated with the fragmentation of the state security apparatus, than to the quantitative increase in organized crime, or a unilateral increase in violence by the bands.State security devices have in Latin America (as in Chile) problematic autonomy levels regarding political power.However, both Durán-Martínez and Trejo and Law (in the case of Mexico), link the loss of cohesion in the state security apparatus with the growing fragmentation and electoral alternation.A similar argument suggests from Los Santos and Lascano (2017) when analyzing the case of the city of Rosario (Argentina), in which violence climbed geometrically in the last decade.

In short, imagine a stage with three elements.First, a safety apparatus of the increasingly illegitimate state in social and fragmented terms, both internally and in its relationship with the political system (see Mónica González column in Ciper).Second, a context of high uncertainty and fragmentation at the political level, coupled with a sustained process of loss of institutional confidence (see abc1 anomia column).Third, the presence of relevant market disruptions, such as those that have generated the expansion of multiple activities associated with organized crime in recent years, or the new competition dynamics that have introduced the context of the Covid-19 pandemic at territorial level.That scenario, which is far from imaginary, resembles a perfect storm.

TO DO?

We can as a society look for the side and continue thinking that here, "institutions work" and that Chile, is also an "oasis" of legality.We can look for scapegoats and blame immigrants, assuming that five or ten years ago, there was no organized crime in Chile.We can also fall into the temptation to think of easy solutions, "silver bullets."The problem is so complex and its dynamic so dizzying, that there are no proven solutions or hand.What we do know, as I will argue in the next column, is the damage that can cause, in this context, the "silver bullets" in which some are thinking.

Notes and references

Andreas, Peter.Smuggler Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America.Oxford University Press, 2013.

Auyero, Javier.The gray zone: collective violence and party political in contemporary Argentina.XXI Century Editors, 2007.

Auyero, Javier, and Katherine Sobering.The Ambivalent State: Police-Criminal Collusion at the Urban Margins.Oxford University Press, 2019.

Bergman, Marcelo.More Money, More Crime: Prosperity and Rising Crime in Latin America.Oxford University Press, 2018.

Dewey, Matías.The clandestine order: politics, security forces and illegal markets in Argentina.Vol. 2045. Katz Editores, 2015.

Durán-Martínez, Angelica.The Politics of Drug Violence: Criminals, Cops and Politicians in Colombia and Mexico.Oxford University Press, 2017.

Grillo, Ioan."The narco.In the heart of the Mexican insurgency. »Ed. Uranus, Barcelona (2013).

Trejo, Guillermo, and Sandra Law. Votes, Drugs, and Violence: The Political Logic of Criminal Wars in Mexico.Cambridge University Press, 2020.

This article is part of the CIPER/Academic project, a CIPER initiative that seeks to be a bridge between the academy and the public debate, fulfilling one of the foundational objectives that inspire our environment.

CIPER/Academic is a space open to all national and international academic research that seeks to enrich the discussion about social and economic reality.

So far, Ciper Academic receives contributions from six studies centers: the Center for Conflict and Social Cohesion Studies (COES), the Center for Intercultural and Indigenous Studies (CIIR), the Center for Research in Communication, Literature and Social Observation (Cycles) of the Diego Portales University, the millennium nucleus authority and asymmetries of power (Numaap), the Observatory of Fiscal Expenditure and the Millennium Institute for Research in Depression and Personality (MIDAP).These contributions do not condition Ciper's editorial freedom.