The forgotten ravines of Telde: The Esquila ravine

The forgotten ravines of Telde

The Esquila ravine

After approaching the Ojos de Garza ravines and the Las Arenas ravine, we have to stop at the Esquila ravine. This is how the updated topographic map of the IDE Canarias (Canary Islands Spatial Data Infrastructure) recognizes the small ravine that flows into Aguadulce beach.

For me it was always the Aguadulce ravine, by toponymic logic, and that is how I reflected it during the study and subsequent publication of the "Ecological path through the sandbanks of Tufia".

The year was 1987 and the demolition of the illegal houses and shacks that occupied the beach, the cliffs on both sides and part of the ravine had recently been demolished. This development was as illegal as it was and still is dozens of them that dot the coastline of Gran Canaria, but in view of the facts not all have suffered the same fate.

Thirty-five years later, I walk through this space again with the intention of scrutinizing every last corner, observing the changes produced in it.

To do this, I start at its source, which lies buried under a road that, perpendicular to the highway, closes off the El Goro industrial area to the south. At the end of it, a ravine generated by the occasional rains has its way through an existing tunnel under the highway. Thus crossing the GC-1, a large-diameter cylindrical pipe collects them to release them in a kind of valley that is currently the head of this short ravine, since it has no entity to consider it a ravine.

On both sides of the river, cultivated land was settled in the past, but thirty-five years ago, in my first journeys along this coast, there was no longer any cultivation in the area. It was, however, a landscape where traces of the irrigation canals remained, the furrows that had given life to the crops were still well defined, and the presence of some cucañas caught my attention. Back then there were more curlews in the area, more calanders and more Moorish birds. Now that I am going through this space again, the transformation in a large part of these lands is enormous. Under the highway, the dilapidated, demolished remains of several constructions associated with storage, machinery rooms, a cistern and tenements speak for themselves of the degree of abandonment suffered by the place. These dilapidated buildings are a danger in themselves, because without a roof and with half-demolished walls the existing risk is considerable, but it is taken for granted that nobody passes through here and it is not like that, because during my recent walks to carry out the present article, young people and fishermen passed through this ravine, coming from La Jardinera or the El Goro industrial estate.

The left slope of the ravine has seen its farmland buried by tons of earth and huge stones until a new profile is achieved, an esplanade on which a company dedicated to construction materials and a new vehicle depot sits. I stop to observe the profound change, the tremendous and impressive vision of a transformed territory. I remain silent and listen, without wanting to, to the eternal and annoying noise of the hundreds of vehicles that circulate incessantly on the highway and I wonder if one day, on this island whose traffic is structured around the great coastal highways, public transport, efficient, economical, silent and non-polluting, it will transport the majority of canaries, who now travel alone in their private car, to their work centers first thing in the morning and back home at the end of the day.

The slope of this aberrant embankment collapses over the meager channel, largely buried, now converted into a huge unstable slope where plants have serious difficulties in colonizing it and the visual impact of this absence of vegetation from the motorway is brutal. Added to this irreversible impact is the dumping that, for decades, trucks loaded with earth, stones and construction debris have carried on the abandoned fields that make up the right slope of the ravine, depositing them in small and large mounds, without order or concert. any, without worrying about how the land is, since surveillance was and is null and absolute permissiveness. There are laws that protect rustic land, even if it is uncultivated -we have mentioned them in previous articles-, there are laws that protect the original landscape, there are laws that oblige owners to conserve the profiles of these soils and make it impossible to turn them into dumps - We have already denounced it in other articles, specifically the one published on February 21 of this year entitled: "Open war against the landscape" -, but they are not applied. Despite existing complaints, a landscape is never restored. Result: a pitiful spectacle.

In what remains of the riverbed, the native flora has lost the battle and it is the invasive botanical species, the cat's tail, that occupies it. Calentones and castor beans complete the rosary of introduced flora. Some sea buckthorns, most of them dry, are surviving remnants of better times.

Only the strip of ravine that is under the road that from the roundabout of the industrial zone of El Goro goes to the urban center of Tufia is saved from these environmental impacts. And it is saved from this manifest impunity, where the abandonment or collusion of the property is joined by the lack of vigilance and rigor in applying the existing laws regarding the protection of rural land by the responsible authorities, because this area of the barranquillo is within a natural space recognized as a Site of Scientific Interest of Tufia. It is this legislative figure who protects the last stretch of the ravine. It is this figure and nothing else, although the shelter of such protection does not appear visually signaled anywhere in the ravine.

So we cross this track and the landscape of the ravine changes radically. The substrate becomes sandy and dozens of well-developed specimens of Schyzogine sericea, the salty white, stand out in the riverbed. It is under them where the greatest presence of animal life is observed, excrements of various species of vertebrates that I cannot identify. Some, I think, I identify as belonging to Moorish hedgehog, others are lizard. White salted ones also thrive on the right slope. It is possible that this is the area where the waters of the occasional rains are concentrated. I base this on the remains of a charcón, a small lagoon of ephemeral duration, where herbaceous plants have developed to occupy its surface. Parallel to this space runs the asphalt track that goes to Tufia, delimited by wooden bollards that make it impossible to park along it and prevent leaving it and illegally accessing the protected area with a vehicle -car or motorcycle-. goes through.

To our left, the abandoned farmland appears covered with cosco, a creeping plant that in the past was used to make soap and its seeds, in times of extreme need, to make gofio. Beyond the cosco, no plant can be seen in these spaces, the soil is so depleted. A dirt track that is very popular with cyclists runs through these vacant lots. It is one of many alternative paths for cyclists as a response to institutional abandonment. Through the Silva ravine and coming from Las Palmas -combining abandoned land, unused agricultural land, shoulders, ravine bottoms, sidewalks... several tracks pass through here that continue along the coast, crossing the Tufia and Ojos de Garza sandbanks, or they run between greenhouses, leaving the protected area to their left and then dispersing to other municipalities in eastern Gran Canaria. This route is the result of the improvisation of multiple bicycle users, an unfortunate consequence of the negligence of the island authorities in providing this strip of the nascent with a cycle route that allows the transit of as many cyclists as there are. It is sad but the empire of the car rules at the insular level and the Cabildo turns a deaf ear to alternative and less polluting proposals. There is a project, there are hundreds of citizens who demonstrated in its favour, but there is no cycle-walking lane linking the most populated municipalities on the island: Telde and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Returning to the channel, outside the influence of the salty whites, isolated specimens of chaparro are identified. There are few, barely half a dozen, but they give hope to the continuity of the species beyond the well-defined sandy area that is located between the Ojos de Garza beach and the Tufia peninsula. We found quite a few specimens of turmeros -helianthemum canariense- on the sandbank of this ravine. Nevadilla in this zone is the dominant plant. Although its appearance is squat and its size is small, its presence generates a landscape of Lilliputian dunes, a curious and beautiful image that fixes the dune substrate.

Further down, in the direction of the beach, the largest dunes are fixed by gorse and saladillos. The sedges join the gorse in the task of fixing the shifting dunes. A continuous fight, the sand covers the plant and the plant thrives on the mobile substrate. New stems, new green shoots, the plant survives and the dune is gaining height. If you look carefully, the snows are joined by the camel herds when it comes to painting the sandy landscape with color.

As we approach the coast, to our left the sandy substratum disappears, revealing the sandstone. Whimsical shapes, small overlaps, tiny tunnels in the calcareous sand enrich the landscape, a landscape devoid of vegetation because the sedimentary substrate does not allow it. Only isolated, emerging from small mounds of sand, the snowdrifts begin the colonization of the sandstone.

If we look to our right, we notice the lack of sand. It is the direct cause of a transformed landscape. In addition to the aggression that the construction of so much illegal housing throughout this space entailed in the first place, the work of demolition and removal of rubble was added. Many years have passed, but the trace of the altered landscape is still there. It is still early for the complete recovery of the place.

While the sands, in this first strip of hillside, do not stabilize as would be desirable, the sandstone and caliche make an appearance, occupying large sectors of it and in those places the erosion gallops and the plants do not prosper. There are no chaparros in this area, some gorse, daring nevadillas seek colonization and it is observed in areas with some sand, isolated sea lettuce. The road pipits make an appearance sooner or later. Always present in these sandbanks, they are, without a doubt, the most common winged joy.

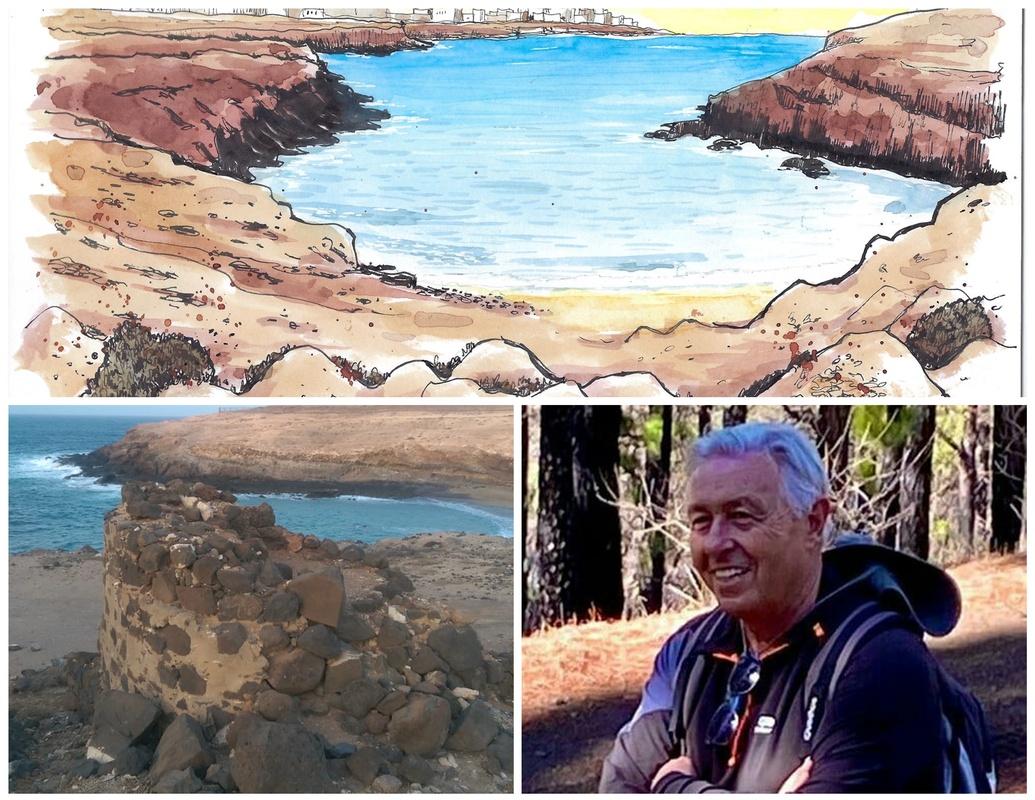

I am now on the beach. Aguadulce's image is reminiscent of a seashell. A seashell where one valve forms the ocean that gently kisses the golden sands and another valve, the upper one, a clear sky that makes it immortal and of extreme beauty. The hinge is the strip of sandstone located behind us and the small walls of pebbles that are found in it. Its scallop shape reminds me that today is the day of Santiago Apóstol, a very special July 25, as it is the Holy Year. While you are reading this article, my steps will have taken me to Tunte or Gáldar, to celebrate it with its people. Both places bring back very vivid and emotionally intense memories. Twinning of towns and communities, Jacobean meetings of cities united by holy paths. Ancestral recipes made with the same basic product, the octopus in a holy year in Tunte. The Plaza de Santiago enveloped in the unmistakable aromas of an extraordinary polbo a feira -translated as Galician-style octopus-, made by pulpeiras from Galicia and the exquisite essences of octopus ropa vieja, a typical dish of our Canarian land. Under the spell of traditional Canarian and Galician music, washed down by wines from both lands: albariños and malvasías, attendees recall an unforgettable tirajanero Santiago Apóstol.

But let's go back to our ravine and our secluded beach. To the left of it, just where the calcareous sand mixes with the pebbles, a mast maintains a red rag. That is where the flag that waved warning that this beach does not have surveillance has remained, in a sad rag, the result of laziness and abandonment because it has not been replaced in many years, on a beach where the flag signage should be taken care of because It does not have a lifeguard service.

Three goros stand out on the beach, made with stones and pebbles present in the place. Its purpose is to protect its users from the wind and sand. I look up to my left and see where an Aboriginal village once stood. It is located at the top of the cliff, in front of the town of Tufia. With difficulty and a great deal of imagination, the remains of what could have been a house are identified, but such is the hodgepodge of stones that were removed in their day, together with those from the stone-cutting of the adjoining land in order to prepare the area for cultivation, that this site is known more from the archaeological records than from the state of its remains. A little further down from this town, descending towards the beach, stands out a half-ruined lime kiln, one more vestige of our industrial past condemned to disappearance and ostracism.

I sit on a sandstone ledge that rises up from the beach. It is the only one that allows us to mitigate the strong solarium, because under it we can enjoy a little shade. At my feet stands a well-preserved goro that encloses a space that, due to its shape and layout, has all the signs of being used not only as a solarium, but also as an area prepared for occasional camping. I look at the sandstones where the overlap is and I read: HUGO, Love, LKS, Vaial, ANA, I love you… They are not the only names or the only references to amorous passion. I also observe various drawings: some that resemble the feet engraved by the aborigines on the mountain of Tindaya, others represent triangles in various positions, some squares, beyond a spiral... Oh! What a bad habit human beings have of leaving their mark wherever they go!

I look a little more at other presences, at other footprints that are not precisely human, and I observe a large number of whitish fossils, of snails of various species, incorporated into the sandstone. Suddenly a slight movement between the small cracks and gaps that the wind has formed in the overlap. -A lizard! -verbalized, astonished. It hides quickly, but there are the traces of its moving tail, those sinuous lines that reveal its presence, but that the wind will quickly erase.

Very close, at my feet, on an imperceptible mound of sand, a small gorse thrives. It is from this year, germinated after the last rains, and the intense green color that it presents surprises me among so many ocher tones of the rest of the plants around it. It is the middle of July and the loss of leaves and the change of color of the stems in preparation for the sweltering heat and drought of a long summer is evident. And despite this, here she is, splendid, true miracle of life. I think that I would like to descend from this flap, approach it and go, with extreme care, removing the sand that is around it until discovering the last of its roots, since it is impossible in such aridity that there is a drop of water capable of causing so much splendor I dismiss such thought as irrational and aberrant, and ponder more logical reasons for so much greenery. I think that, perhaps, the luxuriant green of the small gorse has a lot to do with slowing down, - how sad it is that such a beautiful term has to look for its meaning in a Canarian dictionary because the Royal Spanish Academy does not contemplate it! Anyway…-, that moisture from the sea that runs through these thirsty sandbanks at night.

I tilt my head back and look at the sky. I breathe deeply the essences of the sea and the sand. Flying overhead, several seagulls sway in the air. Silence. I return my eyes to the ground to enjoy another calm look at the beach. To the left of it, in the wet strip defined by the rise and fall of the waves, infinite stars reverberate under the burning sun. It is an optical effect, but it is very beautiful. The beach is only the sand receiving the sea and it is the sea falling in love with the sand until it takes it to its bosom under the promise of impossible nuptials. Just behind, on the small cliff that closes the beach, before beginning the ascent towards the Tufia peninsula and its aboriginal settlement, strata of ash at the foot of it speak of the aborigines and the use of fire in this area. It is not a speculation, it is a true fact, confirmed by archaeologists who have analyzed here, right at the foot of the tide, various stratifications of ashes to learn more about their diet, the marine species that they captured or collected, about pieces of their life daily. Right there, next to these archaeological remains, the remains of a shell midden can be seen.

Magic clears the place, a dream recovered. Blessed is the time to eliminate substandard housing and recover space and air! This is a lonely beach that likes tender, romantic people, lovers of peace and life, but we cannot deny that there are many others unable to read this score of respect and tolerance, of harmony and enjoyment. That is why we see the occasional can of beer or soft drink abandoned by the sands, that is why the marks on the sandstone with names that do not convey anything, that is why the rolling of cars and motorcycles in the area, even though road traffic is totally prohibited, for That's the abandoned masks without any modesty.

From this third article dedicated to small ravines, I draw some conclusions that should be taken into account by those responsible for the surveillance and maintenance of our natural spaces.

1.- It is urgent to delimit with wooden bollards the limits of the Tufia Site of Scientific Interest that encompasses the lower area of the Esquila ravine -which delimits the access road to Tufia and the ocean-, including the remains of the aboriginal settlement and the remains of the lime kiln.

2.- Although it gives a bit of confidence to know that, with very good criteria, this ravine is largely protected within the cartography of the Tufia Site of Scientific Interest, it is urgent to make it visible with vertical posters, since such protection is unknown by the most of the population.

3.- The absolute abandonment of another lime kiln, halfway up the slope, at the mouth of the ravine provokes at least one reflection. Like those we treated in the Ojos de Garza ravine -El Goro furnace-, they should have a minimum study and project for their conservation.

4.- The absolute abandonment in which the remains of the aboriginal settlement are found is more deplorable than on this same slope -left slope-, just at the beginning of the cliff, they lie scattered, forgotten and doomed to disappear. How sad the lack of control over vestiges that should be studied, investigated and preserved! If forty years ago we complained about the generalized abandonment of the archaeological sites present in our municipality, the complaint now extends to the institutional laziness of valuing them -the state of the Morro Calasio archaeological site, which has the largest artificial cavity in the archipelago and a score of caves and this week in this same media their situation has been denounced as it is in the most absolute abandonment-, to turn them into a cultural reference of Telde, to present them to the world as an identity fortress of the first magnitude but, … sometimes I doubt, -and there are many times!-, that there are politicians in the municipality, insular and autonomous, capable of dignifying with their actions the importance and transcendence of our past.

José Manuel Espiño Meilán is a founding member of the Grupo Naturalista Turcón, of which he is currently honorary president, partner and activist. He promoter and defender of life through teaching, ecology, hiking, writing, commitment and patience.